All Things to All People Vol. 15

So, I realize it has been a really long time since I've written here. I've kind of fallen out of the habit of jotting down little bits to write about out and working on them slowly during the week, and on top of that things have been extraordinarily busy for me. This is that brutal time of year when the semester really heats up and Record Store Day looms large on the horizon at almost precisely the same time, and things like sleep and time to reflect (which is really where the genesis of this blog comes from) are in short supply. I'm sure that no one wants to hear about how busy I am, though, so I'll get to it.

I'm sure that by now many of you have seen this article about the current DC hardcore scene that appeared on NPR's web site. Like a lot of people, I was a little bit surprised to see such legit underground music covered by NPR (though it's not unprecedented... my own band No Love has even felt the gentle caress of NPR music), but at the same time there were some parts of the article that annoyed me just a little bit. Now, I realize that writing this may well come off like I'm trying to take some kind of credit for something that I literally have nothing to do with, but I'm going to go ahead and take that risk because it's prompted me to think a little bit about journalism in general and the way that real-life events get subtly distorted in order to fit them into a coherent narrative. That being said, the main passage in the article that bothered me was this one:

Now, there is nothing that is technically factually inaccurate in that paragraph, but it stuck out to me because I've been friends with Connor (Donegan) and Ace (Mendoza) since they were pretty young, and they're both from Raleigh. I mean, at the end of the day who really cares that the middle school referenced in the paragraph above was actually in Cary, North Carolina* and not in the northern suburbs of DC, as the paragraph clearly implies? It is an insignificant detail, but knowing that one particular detail upsets the entire narrative. The author clearly wants to cast this current wave of DC hardcore as a native movement, but it's so much more complex than that. Sure, there were plenty of bands in DC before Connor and Ace moved there, but those two individuals moving to that city clearly provided some kind of spark or catalyst for the current explosion of bands there.

Which leads me to wonder, why did it take two people moving from Raleigh to DC to kick-start this bigger movement? Maybe it was just the show of faith that their move implied. In other words, maybe everyone looked around and said "well, if Ace and Connor thought this scene was cool enough to move here pretty much just for hardcore, then maybe it does have a lot of potential." I have no idea if that's actually the case or not, but it does make sense. Here's another theory that may or may not be true, but also seems to make sense: Connor and Ace, being from the Raleigh area, were imprinted with some of the values and assumptions of the scene here, and bringing those values and assumptions to DC changed that scene. In particular, I'm talking about an attitude toward releasing music on physical formats.

I'm pretty sure Ace and Connor were both around 19 or 20 when they moved to DC, but even though they were so young they both had already played on multiple releases that made it to vinyl. Why? Well, obviously it's partly because they're both very talented and played in good bands, but there are good, talented bands all over the place, only a fraction of which get to release vinyl. However, Ace and Connor happened to grow up in Raleigh, a town with To Live a Lie and Sorry State, two established DIY hardcore labels. Now, I didn't put out vinyl featuring either Ace or Connor (though Will at To Live a Lie did put out the Abuse. LP, which featured both Connor and Ace, and the Last Words LP that featured Connor), but they did grow up in a scene where it was normal--perhaps even expected--for hardcore punk bands to put out vinyl. Again, I have never talked to either of them about this and I have no idea if this is the case or not, but it does seem to me that Connor and Ace brought that attitude toward releasing music with them when they moved to DC. This is interesting because the author of that article clearly views physical (particularly vinyl) releases as an important legitimating factor that not only corroborates the value of the current DC scene, but also separates the now-established bands like Red Death and Protester from the newer crop of bands who, by and large, only have demo releases. But there isn't some secret hardcore board of trustees that decides when your band is good or well-established enough to release vinyl. Putting out vinyl isn't that hard, but it does need to be something that is in the realm of possibility. This is why records always seem to come in waves from certain scenes and/or locations... once someone figures out that putting a record isn't that hard, not only the information on how to do it but also the confidence that you can do it spreads throughout the entire social network.

The author of that article clearly tries to position the current crop of DC bands as some sort of rebirth of the native DIY spirit that spawned the early 80s harDCore scene (despite the fact that the people in the actual bands are clearly reluctant to make this comparison). However, from my particular perspective as someone who is 1. old 2. owns a record label 3. is from North Carolina and 4. happens to know that one little factoid mentioned above, that doesn't really hold water. DC has continued to be DC ever since the early 80s, so why is this explosion of creativity happening now? From my perspective, it seems like Connor and Ace brought a little bit of Raleigh's secret sauce up north. The whole "rebirth of harDCore" narrative is compelling--particularly to an NPR audience who might actually have heard of Minor Threat or Fugazi--however, as the paragraph I quoted above illustrates, it requires a slight distortion of the facts for this narrative to make sense. At the very least it's not the whole story. Who knows how many other similar distortions are in this article, or any other that you might read for that matter? The act of shaping these narratives out of quote unquote "real life" requires us to make these kinds of concessions to simplicity, orderliness, and coherence. No one can write the whole story.

I mentioned to my friend Scott that I felt uneasy with this article, and he just replied, "history is written by the victors." That pithy little idiom makes the writing of history seem like an act of willful distortion or even malice, but this completely benign example that I outlined above shows that that doesn't have to be the case. I'd imagine that it's much more often the case that things work like this... that subtle distortions or omissions allow us to tell a better and/or more coherent story, and those distortions or omissions set us drifting slowly but surely away from the truth.

One of the notes that I have for what I was going to write about in this entry reads, "STUDENTS WHO THINK THEY UNDERSTAND TEXTS VS PUNKS WHO THINK THEY UNDERSTAND RECORDS." I think that I wrote that about three weeks ago and I now have only the foggiest notion of what I was planning on writing about. I think that what I was referring to was this interesting phenomenon I experienced as a literature teacher: the texts that students claimed to like were the ones that they thought they "understood." Whenever I came into class and students told me that they liked something that we had read, I knew that either 1. they had completely misunderstood it, or 2. that they really did understand it and we wouldn't have anything to talk about.

I've always seen it one of my chief objectives as a teacher to foster a sense of curiosity. Students--particularly as they're entering college--tend to see learning as a process of ingesting a piece of knowledge, gaining ownership or mastery of it, and then moving on to the next piece of knowledge. Perhaps that's one way to describe the learning process, but I've always been a fan of intractable problems... of delving deeper and revealing more and more complexity. Consequently, my favorite pieces of literature (not to mention my favorite records) are the ones that I'll never understand. After all, if I "get" something why do I want to bother with it any longer... I won't get anything new from revisiting it. However, when a text reveals itself slowly it warrants more and closer attention I can come back to it again and again because I'm never "done" with it. More than anything, I hope that I leave my students with an appreciation of this feeling... the ability to enjoy being slightly confused.

I believe that I was thinking about this phenomenon as it relates to the life cycle of punk bands. History is littered with flash-in-the-pan bands who are immediately popular because a lot of people have the same reaction that my students have: they like things that they feel like they understand. A derivative band might get popular not simply because they are riding the coattails of a more popular earlier band, but instead because people hear them and "get it" because they've heard it done--to some degree or another, at least--before. Certainly one can point out numerous instances of less innovative bands being more popular than the bands they borrowed a great deal from. I'm sure Pavement's sales numbers dwarf those of the Fall. The mainstream wasn't ready for the Ramones in the late 70s or even the early 80s, but by the time Green Day came around in the early 90s that strain of melodic punk was legible--maybe even comfortable--to the wider public. There is then a further part of the cycle where the general public moves on, the critics reassert control of the narrative and the pioneers get valorized and, ultimately, canonized. Right now Green Day is a nostalgia trip while the Ramones are "serious" music. It's a pattern I see repeated over and over in the history of music and its criticism.

A few weeks ago I watched the above documentary about Twisted Sister and I highly recommend it. I have basically no attachment to Twisted Sister's music, but the documentary was fascinating. What makes it interesting is that it focuses on the now-extinct culture of (mostly cover) bands that played in bars. Cable TV and home video pretty much completely killed the whole idea of going out to see live music for something like 98% of the American public, but seeing live bands used to be a really big part of culture, particularly in certain regions of the US. Interestingly, though, while a band could make a really good living playing sets of mostly covers to hoards of barflies, once you were on that circuit you were branded as a cover band and no matter how good you were, your band was essentially blacklisted from the mainstream record industry. In other words, no one wants to hear a cover band's original tunes. The movie is essentially the story of how Twisted Sister made that difficult and unlikely transition, and it pretty much ends precisely when they finally get the major label contract they had been pining after and working toward for years. It's a really enjoyable documentary and I highly recommend it, particularly if you like a little more than the established Behind the Music narrative from your rock docs.

Anyway, since I picked up this CD player I've gone out shopping for CDs a few times, and it's great. I'm sure part of the fun is the fact that, since I own my record store, I rarely go to other record stores anymore unless I'm traveling. However, I've also really enjoyed the fact that CD-buying is really a much different experience than vinyl-buying these days. Shopping for CDs in the year 2016 reminds me a lot of shopping for vinyl in the 90s. First of all, CDs are cheap... most places sell used CDs for $4-$7, and most of the places that sell used CDs don't seem to bother looking up every single item on Amazon or discogs and trying to sell it in their store for the highest price they see online. Second, the music available on CD is very different than what's available on vinyl. In particular, there's so much 90s stuff that is near-impossible to get on vinyl but is crazy cheap and widely available on CD. Shoegaze is a perfect example... I don't really like much shoegaze enough to pay the premium prices that vinyl commands, but $4 for a Ride CD? Sold!

I really think that CDs are poised to occupy--at least for a time--a much-needed space in the music industry. Buying CDs is a way to have a small investment in a particular title. The structure of subscription services like Spotify and Apple Music, where you pay a flat monthly fee for access to their entire catalog, means that I have no investment in any particular title. I might check something out, and if it doesn't appeal to me immediately I probably won't even listen to the whole thing, much less revisit it. Vinyl, on the other hand, is a huge investment. Because it's gotten so expensive (the good titles anyway), I better damn well like a record before I spend the money to pick it up on vinyl. However, CDs allow me to take a risk in a way that still forces me to engage with the music on a slightly deeper level. If I invested four dollars into this thing I'm going to make some attempt to get some value out of it, but I'm not going to be heartbroken if it's ultimately just not for me.

I realize that, in nearly every case, I'm paying those four dollars despite the fact that I already have access to the very same music through subscription streaming services. Anyone who has spent any time selling music, though, will tell you that there is absolutely nothing logical about music buying habits.

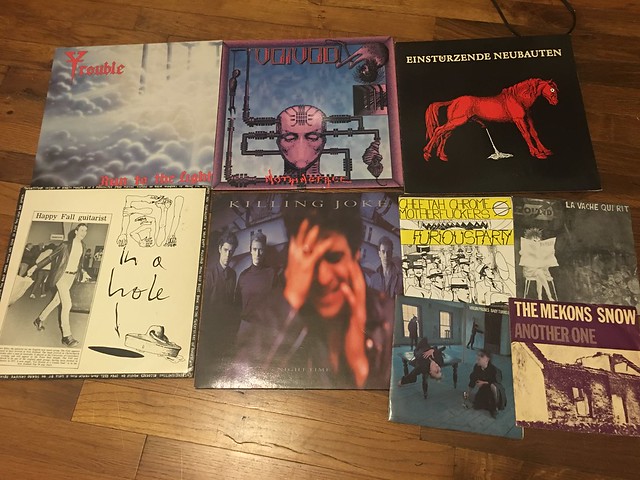

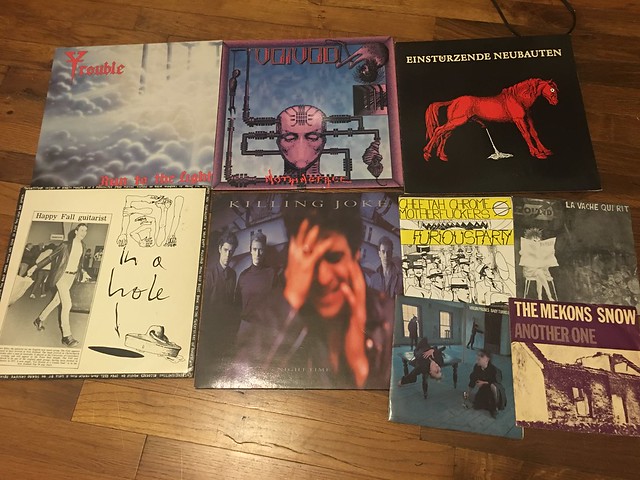

To wrap things up, here's a photo of some records that I've been enjoying, most of which have only recently been added to my collection. Maybe next time I'll muster the energy to write about some of them in more detail, but right now I'm so stressed out that I don't really want to think deeply about music, I just want to sit back and let it wash over me.

I actually don't really know where Ace and Connor went to middle school, but I'm pretty sure they're both from Cary... if it wasn't Cary then I'm almost certain it was in the Raleigh area.

I'm sure that by now many of you have seen this article about the current DC hardcore scene that appeared on NPR's web site. Like a lot of people, I was a little bit surprised to see such legit underground music covered by NPR (though it's not unprecedented... my own band No Love has even felt the gentle caress of NPR music), but at the same time there were some parts of the article that annoyed me just a little bit. Now, I realize that writing this may well come off like I'm trying to take some kind of credit for something that I literally have nothing to do with, but I'm going to go ahead and take that risk because it's prompted me to think a little bit about journalism in general and the way that real-life events get subtly distorted in order to fit them into a coherent narrative. That being said, the main passage in the article that bothered me was this one:

Donegan says the evolution of the scene, and its drastic overlap in band membership, happened organically. The main actors grew up together in those northern D.C. suburbs serviced by the red line train. Donegan and Mendoza went to middle school and high school together and have been playing in bands since they were both 15.

Now, there is nothing that is technically factually inaccurate in that paragraph, but it stuck out to me because I've been friends with Connor (Donegan) and Ace (Mendoza) since they were pretty young, and they're both from Raleigh. I mean, at the end of the day who really cares that the middle school referenced in the paragraph above was actually in Cary, North Carolina* and not in the northern suburbs of DC, as the paragraph clearly implies? It is an insignificant detail, but knowing that one particular detail upsets the entire narrative. The author clearly wants to cast this current wave of DC hardcore as a native movement, but it's so much more complex than that. Sure, there were plenty of bands in DC before Connor and Ace moved there, but those two individuals moving to that city clearly provided some kind of spark or catalyst for the current explosion of bands there.

Which leads me to wonder, why did it take two people moving from Raleigh to DC to kick-start this bigger movement? Maybe it was just the show of faith that their move implied. In other words, maybe everyone looked around and said "well, if Ace and Connor thought this scene was cool enough to move here pretty much just for hardcore, then maybe it does have a lot of potential." I have no idea if that's actually the case or not, but it does make sense. Here's another theory that may or may not be true, but also seems to make sense: Connor and Ace, being from the Raleigh area, were imprinted with some of the values and assumptions of the scene here, and bringing those values and assumptions to DC changed that scene. In particular, I'm talking about an attitude toward releasing music on physical formats.

I'm pretty sure Ace and Connor were both around 19 or 20 when they moved to DC, but even though they were so young they both had already played on multiple releases that made it to vinyl. Why? Well, obviously it's partly because they're both very talented and played in good bands, but there are good, talented bands all over the place, only a fraction of which get to release vinyl. However, Ace and Connor happened to grow up in Raleigh, a town with To Live a Lie and Sorry State, two established DIY hardcore labels. Now, I didn't put out vinyl featuring either Ace or Connor (though Will at To Live a Lie did put out the Abuse. LP, which featured both Connor and Ace, and the Last Words LP that featured Connor), but they did grow up in a scene where it was normal--perhaps even expected--for hardcore punk bands to put out vinyl. Again, I have never talked to either of them about this and I have no idea if this is the case or not, but it does seem to me that Connor and Ace brought that attitude toward releasing music with them when they moved to DC. This is interesting because the author of that article clearly views physical (particularly vinyl) releases as an important legitimating factor that not only corroborates the value of the current DC scene, but also separates the now-established bands like Red Death and Protester from the newer crop of bands who, by and large, only have demo releases. But there isn't some secret hardcore board of trustees that decides when your band is good or well-established enough to release vinyl. Putting out vinyl isn't that hard, but it does need to be something that is in the realm of possibility. This is why records always seem to come in waves from certain scenes and/or locations... once someone figures out that putting a record isn't that hard, not only the information on how to do it but also the confidence that you can do it spreads throughout the entire social network.

The author of that article clearly tries to position the current crop of DC bands as some sort of rebirth of the native DIY spirit that spawned the early 80s harDCore scene (despite the fact that the people in the actual bands are clearly reluctant to make this comparison). However, from my particular perspective as someone who is 1. old 2. owns a record label 3. is from North Carolina and 4. happens to know that one little factoid mentioned above, that doesn't really hold water. DC has continued to be DC ever since the early 80s, so why is this explosion of creativity happening now? From my perspective, it seems like Connor and Ace brought a little bit of Raleigh's secret sauce up north. The whole "rebirth of harDCore" narrative is compelling--particularly to an NPR audience who might actually have heard of Minor Threat or Fugazi--however, as the paragraph I quoted above illustrates, it requires a slight distortion of the facts for this narrative to make sense. At the very least it's not the whole story. Who knows how many other similar distortions are in this article, or any other that you might read for that matter? The act of shaping these narratives out of quote unquote "real life" requires us to make these kinds of concessions to simplicity, orderliness, and coherence. No one can write the whole story.

I mentioned to my friend Scott that I felt uneasy with this article, and he just replied, "history is written by the victors." That pithy little idiom makes the writing of history seem like an act of willful distortion or even malice, but this completely benign example that I outlined above shows that that doesn't have to be the case. I'd imagine that it's much more often the case that things work like this... that subtle distortions or omissions allow us to tell a better and/or more coherent story, and those distortions or omissions set us drifting slowly but surely away from the truth.

One of the notes that I have for what I was going to write about in this entry reads, "STUDENTS WHO THINK THEY UNDERSTAND TEXTS VS PUNKS WHO THINK THEY UNDERSTAND RECORDS." I think that I wrote that about three weeks ago and I now have only the foggiest notion of what I was planning on writing about. I think that what I was referring to was this interesting phenomenon I experienced as a literature teacher: the texts that students claimed to like were the ones that they thought they "understood." Whenever I came into class and students told me that they liked something that we had read, I knew that either 1. they had completely misunderstood it, or 2. that they really did understand it and we wouldn't have anything to talk about.

I've always seen it one of my chief objectives as a teacher to foster a sense of curiosity. Students--particularly as they're entering college--tend to see learning as a process of ingesting a piece of knowledge, gaining ownership or mastery of it, and then moving on to the next piece of knowledge. Perhaps that's one way to describe the learning process, but I've always been a fan of intractable problems... of delving deeper and revealing more and more complexity. Consequently, my favorite pieces of literature (not to mention my favorite records) are the ones that I'll never understand. After all, if I "get" something why do I want to bother with it any longer... I won't get anything new from revisiting it. However, when a text reveals itself slowly it warrants more and closer attention I can come back to it again and again because I'm never "done" with it. More than anything, I hope that I leave my students with an appreciation of this feeling... the ability to enjoy being slightly confused.

I believe that I was thinking about this phenomenon as it relates to the life cycle of punk bands. History is littered with flash-in-the-pan bands who are immediately popular because a lot of people have the same reaction that my students have: they like things that they feel like they understand. A derivative band might get popular not simply because they are riding the coattails of a more popular earlier band, but instead because people hear them and "get it" because they've heard it done--to some degree or another, at least--before. Certainly one can point out numerous instances of less innovative bands being more popular than the bands they borrowed a great deal from. I'm sure Pavement's sales numbers dwarf those of the Fall. The mainstream wasn't ready for the Ramones in the late 70s or even the early 80s, but by the time Green Day came around in the early 90s that strain of melodic punk was legible--maybe even comfortable--to the wider public. There is then a further part of the cycle where the general public moves on, the critics reassert control of the narrative and the pioneers get valorized and, ultimately, canonized. Right now Green Day is a nostalgia trip while the Ramones are "serious" music. It's a pattern I see repeated over and over in the history of music and its criticism.

A few weeks ago I watched the above documentary about Twisted Sister and I highly recommend it. I have basically no attachment to Twisted Sister's music, but the documentary was fascinating. What makes it interesting is that it focuses on the now-extinct culture of (mostly cover) bands that played in bars. Cable TV and home video pretty much completely killed the whole idea of going out to see live music for something like 98% of the American public, but seeing live bands used to be a really big part of culture, particularly in certain regions of the US. Interestingly, though, while a band could make a really good living playing sets of mostly covers to hoards of barflies, once you were on that circuit you were branded as a cover band and no matter how good you were, your band was essentially blacklisted from the mainstream record industry. In other words, no one wants to hear a cover band's original tunes. The movie is essentially the story of how Twisted Sister made that difficult and unlikely transition, and it pretty much ends precisely when they finally get the major label contract they had been pining after and working toward for years. It's a really enjoyable documentary and I highly recommend it, particularly if you like a little more than the established Behind the Music narrative from your rock docs.

Since this blog has already documented the growth of my home stereo system I might as well tell you about the newest addition: a CD player.

Until a few days ago I only owned a few CDs... aside from a handful of Sorry State releases and a few other bits of detritus, my CD collection consisted of the following:

- GISM: Sonicrime Therapy

- Judgement: Just Be

- The Fall: The Complete Peel Sessions

- The Fall: Box Set 1976-2007

Anyway, since I picked up this CD player I've gone out shopping for CDs a few times, and it's great. I'm sure part of the fun is the fact that, since I own my record store, I rarely go to other record stores anymore unless I'm traveling. However, I've also really enjoyed the fact that CD-buying is really a much different experience than vinyl-buying these days. Shopping for CDs in the year 2016 reminds me a lot of shopping for vinyl in the 90s. First of all, CDs are cheap... most places sell used CDs for $4-$7, and most of the places that sell used CDs don't seem to bother looking up every single item on Amazon or discogs and trying to sell it in their store for the highest price they see online. Second, the music available on CD is very different than what's available on vinyl. In particular, there's so much 90s stuff that is near-impossible to get on vinyl but is crazy cheap and widely available on CD. Shoegaze is a perfect example... I don't really like much shoegaze enough to pay the premium prices that vinyl commands, but $4 for a Ride CD? Sold!

I really think that CDs are poised to occupy--at least for a time--a much-needed space in the music industry. Buying CDs is a way to have a small investment in a particular title. The structure of subscription services like Spotify and Apple Music, where you pay a flat monthly fee for access to their entire catalog, means that I have no investment in any particular title. I might check something out, and if it doesn't appeal to me immediately I probably won't even listen to the whole thing, much less revisit it. Vinyl, on the other hand, is a huge investment. Because it's gotten so expensive (the good titles anyway), I better damn well like a record before I spend the money to pick it up on vinyl. However, CDs allow me to take a risk in a way that still forces me to engage with the music on a slightly deeper level. If I invested four dollars into this thing I'm going to make some attempt to get some value out of it, but I'm not going to be heartbroken if it's ultimately just not for me.

I realize that, in nearly every case, I'm paying those four dollars despite the fact that I already have access to the very same music through subscription streaming services. Anyone who has spent any time selling music, though, will tell you that there is absolutely nothing logical about music buying habits.

To wrap things up, here's a photo of some records that I've been enjoying, most of which have only recently been added to my collection. Maybe next time I'll muster the energy to write about some of them in more detail, but right now I'm so stressed out that I don't really want to think deeply about music, I just want to sit back and let it wash over me.

I actually don't really know where Ace and Connor went to middle school, but I'm pretty sure they're both from Cary... if it wasn't Cary then I'm almost certain it was in the Raleigh area.

Skip to content

Skip to content